EMDR (or Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) was developed by Francine Shapiro once she developed the AIP (Adaptive Information Processing) model. According to emdria.org, “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is an extensively researched, effective psychotherapy method proven to help people recover from trauma and other distressing life experiences, including PTSD, anxiety, depression, and panic disorders.”

It is a structured form of therapy that incorporates eye movements (while the client is fully conscious and aware) to process troubling or traumatic memories and experiences without having to talk about them in as much detail.

It is a structured form of therapy that incorporates eye movements (while the client is fully conscious and aware) to process troubling or traumatic memories and experiences without having to talk about them in as much detail.

In a nutshell, eye movements help the brain “heal itself” from disturbing experiences and their effects. It is also usually faster than the traditional talk therapy approach, but the length of therapy depends on the client and the presenting issues. More complex trauma and severe mental illness may require more sessions.

EMDR is based on a three-prong approach of tackling memories, present disturbances, and future actions. The goal is to completely process any experiences that are causing current distress or other problems and then to implement what is needed now for full health and healing.

When all three prongs are processed and implemented, that traumatic memory or experience is considered complete – finished processing. When fully processed (or when the memory is now stored correctly in the brain), it should no longer cause elevated levels of distress or other uncomfortable emotions, body sensations, and unhelpful thinking patterns.

The memories become useful instead of harmful. The brain can move forward and no longer remain stuck in the hurt of the past. “The goal of EMDR therapy is to leave you with the emotions, understanding, and perspectives that will lead to healthy and useful behaviors and interactions.”

EMDR is broken down into eight phases. Not all those phases include eye movements, so here is a brief look at each phase in EMDR.

The Eight Phases of EMDR

Phase One: History and Treatment Planning

This could take one to three sessions, depending on the situation. If a person is coming in to process many memories or if their history is complex, this part could take a bit longer. History-taking can continue throughout treatment, though.

The therapist is looking for past and present family history and relationships, history of the presenting problem, medical history, mental health history, how the presenting problem is manifesting today, and more. During the history-taking phase of treatment, the client can share as much or as little as they are comfortable with.

The therapist is looking for past and present family history and relationships, history of the presenting problem, medical history, mental health history, how the presenting problem is manifesting today, and more. During the history-taking phase of treatment, the client can share as much or as little as they are comfortable with.

During this phase, the therapist also works with the client to develop a treatment plan that addresses each of the past event(s) (or targets for EMDR) that created the current problem, present situations causing distress, and the skills the client needs for his well-being and to manage the problem in the future (the three-throng approach).

Phase Two: Preparation

This may take several sessions, or it may take a few more, depending on the level of trauma history and severity of presenting problem today. During this phase, the therapist teaches the client some methods to handle the strong emotional disturbances they currently deal with and the emotional distress that could arise during eye movements.

They may revisit old coping skills or learn new and more effective skills. The client needs to be able to emotionally handle processing and life after therapy. The goal during the first two phases is to establish trust between the therapist and the client so the client feels safe to move forward.

Without trust, EMDR cannot be effective because the client may not report everything needed during eye movements, and that could hinder processing. This is also when the therapist explains the detail, theory, and process of EMDR, so the client understands what to expect.

Phase Three: Assessment

There are a few different things that happen during the assessment. This is one of the most important phases. The therapist will begin by discussing some key information about each target memory that was listed out in the treatment plan.

This does not mean the client has to go into much detail, but the therapist will need to know more about each memory. The therapist will ask the client to identify a specific image or mental picture that best represents the target memory. The client also needs to share current feelings and body sensations that arise when thinking about the event.

This does not mean the client has to go into much detail, but the therapist will need to know more about each memory. The therapist will ask the client to identify a specific image or mental picture that best represents the target memory. The client also needs to share current feelings and body sensations that arise when thinking about the event.

Then the client chooses a statement of negative self-belief associated with the event. For example, the target memory the client needs to process is an instance of sexual abuse. The person would tell the therapist the one image that stands out about the memory and then share any thoughts associated with it about herself.

The thought could be something like “I am disgusting.” Usually, a person can name these negative thoughts about herself that are not accurate or helpful, but she continually thinks them. This shows that the memory is not resolved. The therapist uses a SUD scale (0-10) to rate the level of disturbance due to the negative belief.

Then the person names a more positive thought that she would like to think about herself in the present, like “I am whole.” The therapist then uses a scale from 1-7 called the VOC (Validity of Cognition) scale to indicate how true that new positive statement feels at this present moment. The goal of the following phases is for the SUD level to decrease and the VOC score to increase.

These first three phases lay the groundwork for the eye movements (or tapping or tones), and it helps the client and the therapist to pay attention to progress in the next phases. There are no eye movements (or tapping, tones) in the first three phases.

Phase Four: Desensitization

During this phase, the therapist guides a person through a series of eye movements (or tones or tapping). One of the target memories is the focus, and the client’s thoughts, emotions, and body sensations are measured with the SUD and VOC scales. The therapist will also help deal with any other memories that surface during the reprocessing of the target, as well as any insights that may arise.

The client does not have to describe in detail any disturbances but will give the therapist some information to continue to move the memory into complete resolution. This phase can also help deal with other issues that may have arisen due to the traumatic event.

Phase Five: Installation

In phase five, “the goal is to concentrate on and increase the strength of the positive belief that the client has identified to replace his or her original negative belief.” The eye movements (or tapping or tones) will continue until the VOC score increases to a level seven (completely true).

In phase five, “the goal is to concentrate on and increase the strength of the positive belief that the client has identified to replace his or her original negative belief.” The eye movements (or tapping or tones) will continue until the VOC score increases to a level seven (completely true).

The client begins with a mental image or picture that contributes to the negative belief previously shared in phase three, or the client focuses on the negative belief itself. The therapist will lead the client through another series of eye movements. The positive beliefs (from the previous example) “I am whole” or “I am pure” (or whatever it is for the specific situation) will be focused on until the client genuinely believes it.

Phase Six: Body Scan

Once the positive cognitive or thought is installed, the client will then focus on the original memory or target and notice if there is still any tension in the body. If there is still any tension, the therapist targets it for reprocessing and goes through another series of eye movements. A session is not complete if there is still tension in the body.

Phase Seven: Closure

This is what happens at the end of every session (during the reprocessing phases 4-7). During this phase, if the traumatic target memory is not fully resolved, the therapist prepares the client for starting again next session, walks through some calming techniques so that the client can leave in a stable place, and the therapist prepares the client for any distress that may arise in between sessions and how the client can handle that.

Phase Eight: Reevaluation

The reevaluation phase begins each session to assess the treatment plan and any targets that need to be addressed, as well as evaluating how the client has been doing since the last session and any distress that came up during the week.

EMDR is meant to be a shorter, more effective form of treatment for not only PTSD and trauma but many other problems. It is essential only to do EMDR with a trained professional who follows the eight phases so that treatment does what the client needs.

References:

emdria.org/about-emdr-therapy/experiencing-emdr-therapy/

Photos:

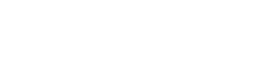

“Group Therapy”, Courtesy of RODNAE Productions, Pexels.com, CC0 License; “Stressed”, Courtesy of Kindel Media, Pexels.com, CC0 License; “Sunset”, Courtesy of Szabolcs Toth, Pexels.com, CC0 License; “Cliche”, Courtesy of Tara Winstead, Pexels.com, CC0 License

-

Kate Motaung: Curator

Kate Motaung is the Senior Writer, Editor, and Content Manager for a multi-state company. She is the author of several books including Letters to Grief, 101 Prayers for Comfort in Difficult Times, and A Place to Land: A Story of Longing and Belonging...